The state agency that reviews instances of teacher misconduct has more cases on its plate than at any point in at least a decade. “The system was not designed to manage this kind of volume,” the head of the agency said late last year. “It just wasn’t.”

by Kayla Jimenez

The state agency that reviews instances of teacher misconduct is juggling more cases than at any point in more than a decade.

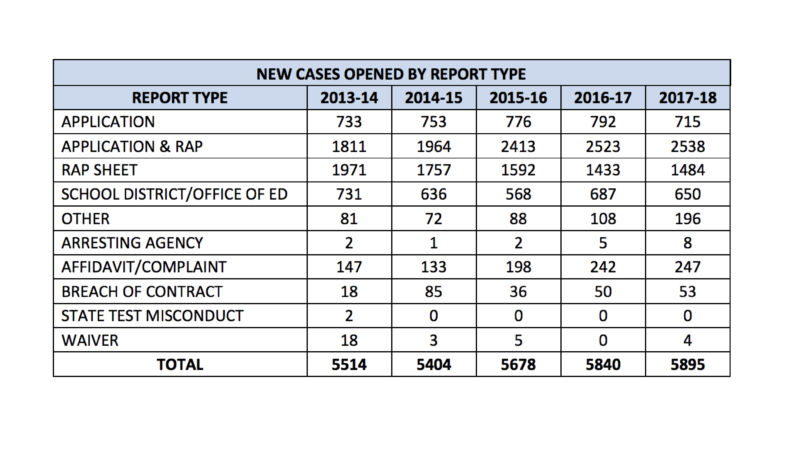

The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing received 5,895 misconduct cases last year – 400 more cases than it received five years ago and the highest number of instances of misconduct reported since at least 2007. Records going beyond 2007 were not immediately available.

The rise has created a higher workload for the commission, which can delay the adjudication process for each case. The resulting lag often allows problem teachers to remain in classrooms, often as substitute teachers, for years while the commission investigates whether to revoke their credentials.

More than half of all reported misconduct cases come from credential applicants – people trying to obtain a teaching credential – and the rest are by credential holders, including teachers and administrators. The highest number of reports come from new credential applicants who falsely disclose no history of a criminal background, credential holders who are reported to the commission for committing a crime.

The fourth highest number of reports come from school districts reporting their own employees or former employees. Twelve percent of all misconduct reports last year were made by school superintendents – up from just 3 percent nine years ago.

The number of cases reported to the commission began to surge in February 2012, “due to some highly publicized cases of misconduct,” according to the commission’s latest annual workload report.

Joshua Speaks, a spokesman for the commission, said one those was a widely covered sexual abuse case at Miramonte Elementary School in Los Angeles. The highest number of cases originate from Los Angeles Unified School District, the largest district in the state.

Image courtesy of the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing

“The school district was sued,” Speaks said of the Miramonte case. “There were superintendents who had not been reporting, which is a criminal offense. If a superintendent does not report, the CTC can revoke a superintendent’s credential.”

School superintendents are required by state law to notify the commission within 30 days any time a credential holder’s employment status changes as a result of an allegation misconduct, or while an allegation is pending.

That includes when an employee is dismissed, not re-elected, resigns, is suspended or placed on unpaid administrative leave as a final adverse employment action for more than 10 days, retires or is otherwise terminated as a result of an allegation of misconduct or while an allegation of misconduct is pending.

If a superintendent fails to comply, an arm of the committee can investigate him or her for unprofessional conduct.

San Diego County school districts with the highest number of misconduct reports to the commission are San Diego Unified School District, Sweetwater Union High School District, Oceanside Unified School District, Grossmont Union High School District and Chula Vista Elementary School District, according to data on each California school compiled by the CTC between 2008 and 2018.

Voice found that some data provided by the commission did not match school district data contained in its annual report. Some smaller districts in the county are missing from the report, which might be because they have never reported misconduct to the commission, Speaks said.

He said the commission was reviewing and manually re-running its data to understand the discrepancy. “Unfortunately, the manual review is very time-intensive,” he said.

Speaks said the increase in misconduct reports does not necessarily mean there is a rise in actual misconduct. The surge in cases could, he said, reflect that more superintendents are reporting misconduct by their employees after becoming aware of the ramifications of withholding reports, among other factors.

Complaints from the public, called affidavits, have risen 53 percent since 2014-2015. “This may be attributable to the commission’s user-friendly website. The public can now easily access complaint forms under the Educator Discipline tab,” according to last year’s annual workload report.

Speaks said complaints must be from made from a person with first-hand knowledge of the misconduct. If misconduct was committed against a minor student, the report must be made by the student. The commission cannot open a case made by a parent or guardian.

The commission uses seven categories to distinguish misconduct: alcohol, other crimes, serious crimes and felonies, drugs, child crime non-sexual, child crime sexual and adult-sexual.

The highest amount of all misconduct case reports – more than 40 percent – are related to alcohol. About 7 percent of reported cases are related to sexual crimes against children and adults, the lowest amount of reports.

Image courtesy of the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing

About half of all cases reported to the commission move on to be reviewed by the Committee on Credentialing – a seven-person volunteer committee that meets once a month for up to three days – to determine whether the subject of the complaint should keep his or her credential.

The remaining cases are delegated to the commission’s staff on the front line to close if they meet specific criteria, such as a case that involved a single alcohol-related offense, like a DUI, that did not impact children or schools.

The committee currently has 2,825 cases to review, according to a February report by the commission. The number has increased by more than 600 cases in the past six years. The committee reviews an average of 105 misconduct cases per month.

“The large increase in volume is a result of the upsurge in applications submitted by both applicants and first-time applicants,” the annual workload report says. “Despite these increases, cases continue to be processed timely.”

But a November report says the monthly caseload may soon exceed 3,000 cases – a substantially higher number than the monthly caseload following the 2011 audit.

It says that in September 2018, commission members expressed concern about the group’s ability to take on more cases, citing burnout and a desire to avoid an escalating backlog.

“This continued triage is not sustainable, as the committee process is becoming severely overburdened by the volume of cases,” it reads.

Speaks previously told Voice the commission will have to identify further efficiencies or hire more people to handle its increasing workload.

Mary Vixie Sandy, executive director of the commission, said in a November meeting that the committee does not see a decrease in the numbers of open cases coming before the committee in the near future. She said it is a significant issue in terms of managing the workload and maintaining an equilibrium – opening and closing the same number of cases per year.

“Essentially the conclusion we are drawing is … the system was not designed to manage this kind of volume,” Sandy said. “It just wasn’t.”

Originally appeared in Voice of San Diego

Kayla Jimenez is a reporter for Voice of San Diego. She writes about education, schools and children in San Diego County. Kayla can be reached at kayla.jimenez@voiceofsandiego.org.

(909) 335-8100 ·

(909) 335-8100 ·  (909) 335-6777

(909) 335-6777 Email:

Email: