By Allison Griner, Global Reporting Centre

Over more than a decade, Lai Yun got to know the Chinese town of Guiyu through his work as an environmental activist. He breathed its acrid air, squinted through its soupy smog and marveled at its jet-black river.

He also photographed the source of that pollution: mountains of old electronics piled so high that they spilled onto the town’s streets, their innards splayed out, ready for workers to pick apart and recycle by hand.

So it was hard for him to recognize the place when he returned in December 2015. Guiyu, the town that had rocketed to infamy as one of the world’s biggest electronics graveyards, was suddenly, almost miraculously, clean.

“Today,” Lai says cautiously, “Guiyu looks like it’s better.”

How this change happened, and why, is a story that spans decades and international borders. It’s also not the full picture. Lai recognizes, as a visit to Guiyu in August confirmed, that looks can be deceiving.

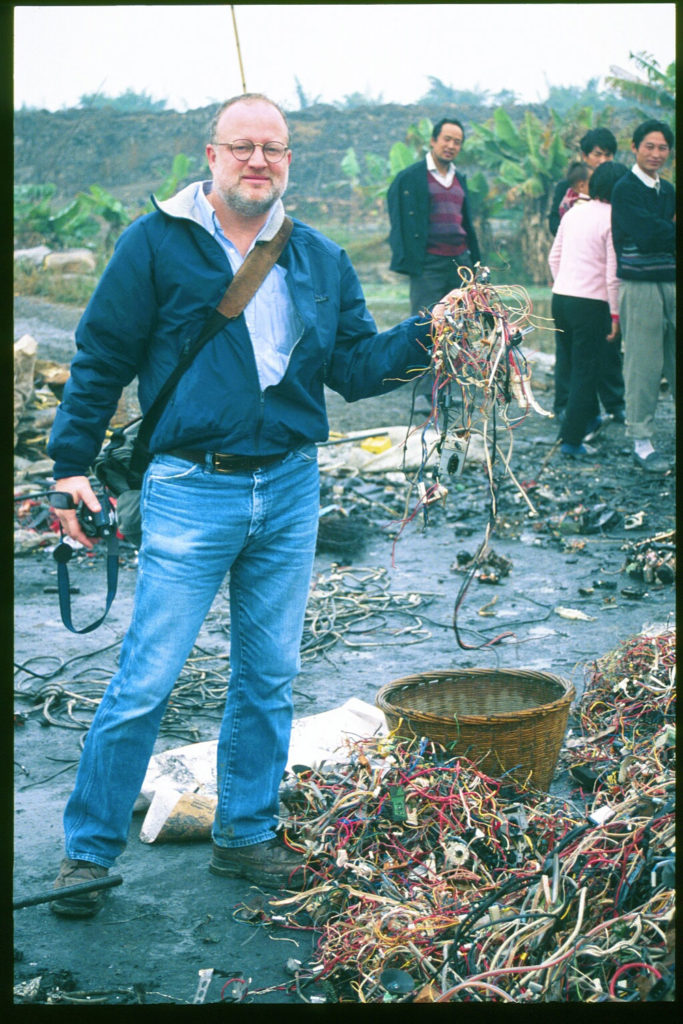

Lai Yun, a Chinese environmental activist, worked for Greenpeace investigating a toxic underground industry: the international trade of electronic waste.Credit: Allison Griner/Global Reporting Centre

Lai is part of a generation of Chinese environmentalists born on the cusp of their nation’s modern prosperity. But the wealth carried a harrowing cost: widespread pollution. Witnessing those changes inspired Lai to work for Greenpeace. There, he started to investigate a toxic underground industry: the international trade of electronic waste.

Seattle-based activist Jim Puckett already was hot on the trail.

“We had heard rumors in the United States that a lot of the electronics that were being collected by so-called recyclers were just being shipped off to China,” Puckett says. He didn’t know where it all was going, just why.

Devices such as printers, TVs and cellphones might seem harmless. On the inside, though, they contain toxic cocktails of chemicals and heavy metals. That makes them expensive, and sometimes dangerous, to dismantle.

Rather than handle what they collect stateside, some American recyclers ship their electronics to places without rigorous health and safety laws. That violates a 1989 treaty called the Basel Convention that bars the trade of hazardous waste across international borders. It explicitly targets “dumping from the richer countries to poorer countries” least equipped to deal with it, Puckett says.

He started a watchdog organization, the Basel Action Network, to help enforce the convention. The United States never ratified that treaty. It’s the only developed country in the world that hasn’t – and it’s the world’s largest producer of e-waste per capita. Tracking its electronic waste has become an international game of whack-a-mole as the illegal trade shifts from place to place in the developing world.

In 2001, Puckett and his colleagues in China finally zeroed in on the epicenter of the smuggling operations in Guiyu, a modest town of 150,000 not far from the South China Sea.

There, he saw tens of thousands of migrant workers tear electronics apart with little more than their bare hands. Others plunged metal-laced microchips into vats of acid, and women cooked circuit boards over coal fires to melt away lead. Plumes of orange gas erupted from the processing. With each smashed monitor and each gutted printer, lead, mercury and other heavy metals entered the environment.

Puckett often is cited as one of the first foreigners to find out about the situation. He, Lai and other environmentalists persuaded Western media to pay attention. Their work generated features on Guiyu’s crisis by CNN, “60 Minutes” and The New York Times.

Often, foreign pressure rankled the people it was meant to help. Migrant workers, who credited the e-waste industry with lifting them from poverty, believed the attention threatened their livelihood.

But the situation threatened their future in other ways, too. Researchers warned that the heavy metals workers handled – such as lead, mercury and cadmium – could attack their nervous systems or cause birth defects in their children. Those health effects can unfold over years.

“Those workers, they come from poor areas, so they only focus on their short-term survival,” says Shan Shan Chung, a biology professor at Hong Kong Baptist University who has studied the health effects of e-waste. “When you are really poor, you don’t care what will happen to you several years down the road.”

With Puckett, who spent 14 years focused on Guiyu, local officials used stalling tactics.

“So many times,” he says, “we would hear from authorities: ‘Don’t worry. It’s being cleaned up.’ ”

Then, in December 2015, the informal scrap industry disappeared from Guiyu’s streets almost overnight.

The local government had issued an ultimatum, ordering all e-waste businesses to relocate to an industrial park on the edge of town. Failure to comply would result in punishment, including steep fines.

In China, tens of thousands of migrant workers tear electronics apart with little more than their bare hands. With each smashed monitor and gutted printer, lead, mercury and other heavy metals enter the environment.Credit: Allison Griner/Global Reporting Centre

Industrial park officials made a point of inspecting all incoming cargo to weed out forbidden foreign electronics, too. The message was clear: Guiyu no longer would be America’s digital dumping ground.

This change came to Guiyu amid a larger movement in China under President Xi Jinping. The leader, often characterized as a strongman, set out to reverse the environmental screw-ups that had earned China so much negative attention. His administration went so far as to “declare war” on pollution.

“I believe that finally that message filtered down to the state level and to the local level,” Puckett says.

Still, when Lai and Puckett made an impromptu visit to Guiyu in December 2015, they found dirty practices happening inside the industrial park.

“The business in this industrial park looks like the same, uses the same technology, uses the same methodology,” Lai says, noting that when he was there a year ago, workers still cooked circuit boards over open flames and breathed in toxic fumes from that process. “So I think it’s a pity. It’s not a real upgrade.”

A visit to the industrial park eight months later revealed many of the same problems Lai first reported. Workers sat on the concrete outside the complex’s gray block buildings, ripping apart old computers as they did in the old days.

A few wore gloves. Even fewer wore masks. An acrid smell filled the air.

Seattle-based activist Jim Puckett started the Basel Action Network to help enforce a 1989 treaty that bars the trade of hazardous waste across international borders. The U.S. is the only developed country in the world that hasn’t ratified the treaty.Credit: Courtesy of the Basel Action Network

One of the workers, Xiao Qiong, explained that money is a big reason she remains in the industry. She says she earns the equivalent of $600 a month, 10 times her previous salary as a waitress.

She, like many workers at the industrial park that day, chose not to wear a mask. The smell from the fumes, she says, “is not that strong, and it’s too hot.”

Her husband, Li Pan, knows environmentalists such as Lai through his work as a local driver for hire. Although Li is aware of the potential health hazards, he and his wife express greater concern for the town’s economic future.

He fears the high costs of working at the industrial park will drive away recyclers. “I am afraid the e-waste dismantling industry is going to disappear,” he says.

Guiyu now deals exclusively with e-waste produced in China – a country set to overtake the U.S. as the world’s biggest electronics consumer.

Since the e-waste trade shifted to different parts of China and other developing countries such as Pakistan and Mexico, global focus on Guiyu has waned. Even Lai, one of the foremost experts on Guiyu’s e-waste problems, has moved on: Greenpeace shut down its e-waste campaign in China, and he’s established another environmental organization that focuses on educating children.

Puckett fears that few advocates remain to carry on the fight. He warns that Guiyu’s environmental struggles are not over.

“It will take centuries,” he says, “for it to clean itself up.”

Originally appeared at revealnews.org