By Amy Julia Harris

The God Loophole: Thousands of religious day cares across America legally are allowed to run their facilities with little government oversight. But freedom from regulation can come at a high price for children. And when things go wrong, parents have little recourse.

Like many parents, when Juan Cardenas began looking for a day care for his 1-year-old son, Carlos, he relied on word-of-mouth. A friend recommended Praise Fellowship Assembly of God in Indianapolis.

Cardenas never had planned to put his baby in day care, so he didn’t know the questions to ask. He just knew Praise Fellowship was a church. He is devoutly Catholic, so he trusted that.

“I thought they were going to do a good job because they served God,” he said.

Almost immediately, Cardenas noticed things were amiss. One day, he arrived to pick up Carlos and found the children waiting in the dark. When he asked why, someone at the day care threw the question back at him: “Do you want to pay for the lights?”

That’s when Cardenas decided Praise Fellowship wasn’t going to work out after all. He found another day care in the area, and Carlos was set to start the next week.

He never made it.

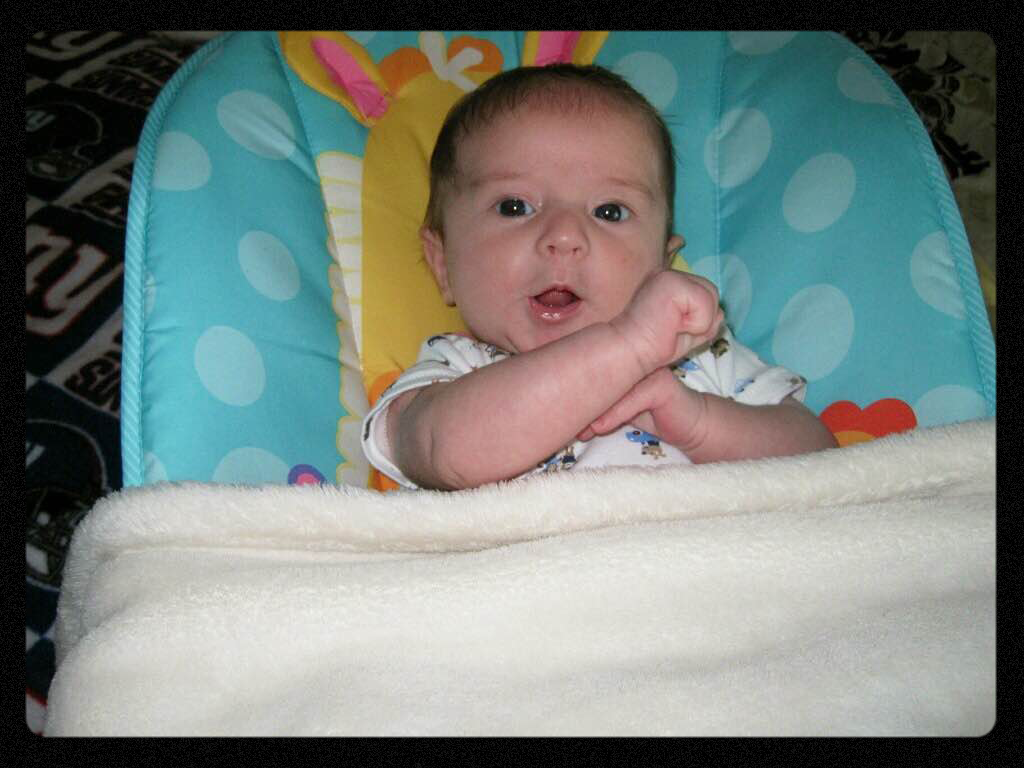

On Feb. 22, 2012, Juan Cardenas got a call from his girlfriend with disturbing news: Their 1-year-old son, Carlos, was missing at his Indianapolis church day care.Credit: Courtesy of Juan Cardenas

What happened next wasn’t an inexplicable tragedy. An investigation by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting found it might have been an avoidable disaster.

On Feb. 22, 2012, as Cardenas sat at his desk at a medical lab, his cellphone rang. It was his girlfriend, Maricela Serna, with disturbing news: The church had called. Their son was missing.

“Is that even possible?” Cardenas thought as he called the day care. A worker told him to calm down. They were looking for Carlos.

The day care was understaffed that day – with only four or five workers caring for at least 50 children – and somehow, the women in charge lost track of Carlos. A supervisor later admitted that “there was no system to know where each child was supposed to be and which staff member they were supposed to be with.”

This isn’t about religion and people’s faith. It’s about common sense and protecting children.”– Gail Piggott

Alabama Partnership for Children

At most day cares across the country, workers are required to always be within sight and sound of the children. But Praise Fellowship wasn’t like most day cares. Because it’s attached to a church, it is absolved from most of the rules designed to keep kids safe.

Sixteen states have carved out exceptions for some faith-based day cares. Freedoms vary from state to state, ranging from the minor, such as waiving a registration fee, to the extreme, where religious day cares aren’t licensed and follow virtually no rules.

Six states are particularly hands off: Alabama, Indiana, Missouri, Florida, North Carolina and Virginia offer religious day cares the most leeway.

Religious groups in these states have argued successfully that regulating their day cares violates the separation of church and state. The religious exemption has become increasingly popular in places where churches most adamantly reject government interference: In Alabama and Indiana, records show almost every other day care is exempt.

Religious advocates suggest parents need not worry about the lack of oversight because day cares are guided by a moral authority that eclipses any regulatory agency.

“We feel like our responsibility for the well-being of those kids is to God,” said Robin Mears, executive director of the Alabama Christian Education Association, which pushed for that state’s religious exemption in the 1980s. “We’re going to answer to him.”

Horrible accidents can and do happen in licensed day cares. But unlicensed religious facilities are off limits to most government regulators, and when problems do arise, parents may have little recourse. Without rules, none have been broken.

Religious day cares get freedoms that are unthinkable at their secular counterparts. At some, workers don’t have to know CPR or have any child safety training. At others, they can whip and spank children. Still others, like Carlos’ day care, do not require workers to be able to see and hear the children they are paid to watch.

The religious exemption baffles child care experts. Gail Piggott with the Alabama Partnership for Children has been fighting to regulate religious day cares for years.

“This isn’t about religion and people’s faith,” she said. “It’s about common sense and protecting children.”

Many faith-based day cares choose to be licensed, following the same standards as secular facilities. But day cares have a financial incentive to seek the religious exemption: Less regulation means lower costs because they can hire fewer workers, offer little or no staff training, and rarely face the upgrades that government inspectors require.

Often, Reveal found, religious day cares cater to low-income parents who are desperate to save money and trust any institution associated with the church.

But freedom from government regulation does not stop thousands of religious day cares from collecting millions of dollars a year in government funding to care for poor children. In the states with the broadest exemptions, these day cares amassed almost $323 million in government child care subsidies from 2011 to 2014, according to available data from five states.

Limited oversight means problems are hard to track. But in the available records, Reveal found that freedom from regulation can come at a high price for children.

- Babies at religious day cares in Indiana languished in dirty diapers for so long that their bottoms became blistered and bloodied, and children wandered alone onto busy highways. Parents detailed these and other problems in 1,800 complaints filed with the state between 2007 and 2014. But in one-third of these cases, child care regulators informed parents that their concerns fell outside the state’s legal purview. “Supervision,” they wrote again and again, “is not required in a ministry.”

- Investigations from Missouri’s child care licensing division show children there were put in dangerous situations dozens of times from 2010 to 2014. Understaffing was a common theme. At one religious day care, a pair of 3-year-olds escaped from the day care and later were found in the rain by police; at another, workers said toddlers weredrugged with Benadryl to knock them out for naps and keep them quiet. One 5-year-old boy was forgotten in a van, where he could have suffocated, and told investigators: “No windows open. No air. I got sweaty.” Records show that many of these dangers sparked little more than a slap on the wrist from the state, such as a requirement that the facilities update their parent handbook.

- Children in Alabama faith-based day cares were so poorly supervised that one disabled girl was left to soak in her own vomit until her mother arrived and another 6-year-old was trampled so hard by an older classmate that he developed a brain injury and had three teeth knocked loose, according to parent complaints filed with the state’s two largest counties since 2010. The Alabama Department of Human Resources, the agency that licenses secular day cares, had no power to investigate, let alone shut down any of these religious day cares for shoddy care. Local law enforcement agencies and health departments can investigate problems, but many of the issues parents complained about broke no rules.

***

As soon as Juan Cardenas heard his son was missing, he jumped into his car, his mind racing. When he finally slowed down, he started praying. “God, whatever happens, he’s in your hands,” he remembers thinking.

Juan Cardenas relied on word-of-mouth when he chose to place his son, Carlos, in a religious day care in Indianapolis. “I thought they were going to do a good job because they served God,” he said.Credit: Chris Bergin for Reveal

Yet he still felt sure it was all a big mistake.

Near the day care, he spotted an ambulance heading the other way. He wanted to follow it, but didn’t. “Carlos is in the day care, not the ambulance,” he thought. He had to be.

Swarms of police officers surrounded the washed-out brick church as Cardenas pushed his way inside. One woman broke through the fray and approached him.

“Carlos died,” she said.

Cardenas dropped his cellphone. He was in shock.

“It was your job to watch Carlos,” he remembers stammering. “I don’t know how this happened.”

In court records, Praise Fellowship workers said Carlos was last seen in the cafeteria around lunchtime. They think he toddled out of the cafeteria’s double-wide doors, down a hallway into a playroom and then into the church sanctuary – undetected.

A religious day care in Indianapolis voluntarily shut down two days after 1-year-old Carlos Cardenas died while in its care.Credit: Courtesy of Juan Cardenas

No one knows why he made his way to the baptismal font behind the preacher’s pulpit. Perhaps a glint of water caught his eye? Somehow, he fell in.

In 2 feet of holy water, which promises eternal life, Carlos drowned.

Lacking supervision

While the supervision and staffing rules at Carlos Cardenas’ day care were minimal, at hundreds of other religious day cares, they are nonexistent.

Many faith-based day cares in Alabama, Indiana and Missouri don’t have to meet any required staff-to-child ratios, for instance. In these states, more than 20 percent of the 2,000 complaints about religious day cares reviewed by Reveal involved not keeping track of children.

At the 900 unlicensed religious day cares in Alabama, there are no state requirements about supervision whatsoever. Workers don’t have to be in the same room as children, leading one toddler to chase children around his day care with a butcher knife and another to inhale unsafe amounts of lighter fluid, according to licensing complaints.

Secular day cares in Missouri must follow strict rules about how many children each worker watches. At least one worker is in charge for every eight 2-year-olds, for instance. But religious day cares get to decide how many children each worker supervises – and those ratios usually are below what the state recommends.

What’s more, licensing investigations from 2010 to 2014 found that 35 Missouri religious day cares skimped on staffing and violated the loose ratios they set for themselves.

"No parent can imagine seeing their son dead. That’s what they put me through.”– Juan Cardenas

Carlos’ father

In one case in Joplin, a 5-year-old boy flipped out of his play car and hit his head. His teacher took a cursory look at the boy, told him to stop crying and went back to caring for 16 children by herself. That was far more children than she was supposed to be watching – the church had told parents that one worker would care for a maximum of 10 kids in that age group.

Later in the day, the boy was lethargic and sleepy. His symptoms were so noticeable that when his mother came to pick him up, she rushed him to the hospital. A doctor diagnosed the boy with a concussion.

Missouri licensing officials were frank in their assessment. They wrote that the boy was injured “due to the fact that (his teacher) was caring for more children than the staff/child ratio submitted in the facility’s Notice of Parental Responsibility.” The day care fired the teacher and was warned that it had to be honest with parents about its actual staff-to-child ratio. But officials had no power to require the facility to hire more workers.

Few training requirements

Betsy Cummings didn’t think to ask about staff qualifications when she enrolled her son, Dylan, at the day care at Bethel Temple Church of Deliverance in Virginia.

All Cummings, a Navy boatswain’s mate, knew was that Tammy Futrell’s day care in Norfolk had no waiting list and was run by a church. That was enough.

Cummings’ Navy job had limited maternity leave, so she started Dylan at Little Eagles Day Care when he was just a few weeks old.

May 25, 2010, Dylan’s third day at Little Eagles, was his last.

Betsy Cummings didn’t think to ask about staff qualifications when she enrolled her son, Dylan, at Little Eagles Day Care. One worker later testified that she never had been trained on how to care for children.Credit: Courtesy of Betsy Cummings

That morning, Dylan’s day care worker, Dinnetta Feeney, placed him face down in his metal crib with a loose-fitting sheet, according to court records. That violates recommended national safety standards that suggest tight-fitting sheets in cribs to avoid accidental suffocation.

Dylan began to cry and fuss. Another worker later would recall that he was struggling to catch his breath.

But Feeney didn’t seem to notice. She picked up Dylan again, then laid him back down on his stomach. She draped a blanket across his legs, turned on music and started a portable floor fan in the stuffy electrical storeroom. Then she went to lunch in a room on the other side of the church sanctuary. Investigators would measure the gap: She was 53 feet away from Dylan’s crib.

Two hours after she put Dylan to bed, Feeney returned to the 12-by-12-foot room to check on him. He was blue and lifeless.

There was vomit and blood on Dylan’s sheet. Liquid was seeping from his mouth and onto his brown T-shirt, which read, “Beary Cute.” When Feeney touched him, he was cold and clammy.

She screamed for help.

Dylan Cummings died on May 25, 2010, after his workers left him alone in a stuffy storeroom at Little Eagles Day Care in Virginia. He was less than 8 weeks old.Credit: Amanda Voisard for Reveal

None of the staff on duty were certified in first aid. A janitor was the only one who knew how to perform CPR. He tried again and again to revive Dylan, but it was too late.

Cummings found out about Dylan in the same way Juan Cardenas heard about Carlos: She got a desperate phone call at work and rushed to the day care.

At Bethel Temple, a paramedic told Cummings that her baby had stopped breathing.

She collapsed and began to cry uncontrollably. As she lay sobbing on the floor, she remembers someone from the day care stroking her back, muttering, “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus,” over and over again.

Preliminary results from the medical examiner indicated that Dylan had suffocated. His death later was ruled sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS.

Dylan Cummings died in this crib in May 2010 at Little Eagles Day Care in Norfolk, Va. He had been placed face down on a loose-fitting sheet – practices that violate national safety standards and increase the risk of sudden infant death syndrome.Credit: Norfolk Circuit Court

Workers at licensed day cares in Virginia have to take 16 hours of training each year, which often includes the dangers of SIDS. They learn that infants never should be placed on their stomachs and that loose-fitting sheets pose a hazard to children. Warm rooms, like the one where Dylan was, also are a risk factor for SIDS.

Feeney later would testify that she never had been trained on how to care for children. Aside from ensuring that staff know how to change diapers and tell whether a child is sick, faith-based day cares in Virginia don’t have to train their staff about child safety.

Interviews revealed it was standard practice at Futrell’s day care to place infants on their stomachs for napping – even a baby such as Dylan, whose mother was aware of the dangers of SIDS and had asked for him to be laid on his back. Half of the 10 infant cribs at Bethel Temple had loose-fitting sheets.

Religious day cares in Alabama, Indiana and Missouri also require little to no child safety training for their workers, leading to dozens of serious injuries. At secular day cares, all staff must be trained.

At one church in Indiana, a parent said that when she picked up her son, he was running a fever. Staff told her that earlier in the day, they had found the boy lying on the floor in the bathroom. But they sent him back to his classroom and “took no action to address the illness,” according to licensing notes.

In Missouri, a 2-year-old girl broke her collarbone at Stepping Stones Child Care Center, but none of the staff realized what had happened. She was crying for hours, whimpering during naptime and saying, “Ow,” but workers did not think there was cause for alarm, according to investigation notes. When the child’s mother picked up her daughter five hours later, she noticed the girl’s shoulders were uneven. She rushed her daughter to the emergency room, where doctors diagnosed a severe collarbone fracture.

Tammy Futrell, the owner of the day care Dylan attended, had a history of being lax about training. When she ran a nonreligious day care out of her home, Futrell had tangled with state regulators.

State inspectors found in 2004 that neither Futrell nor her daughter had completed the hours of training required for licensed facilities in Virginia. Futrell was nine hours short. Her daughter, Angel Hoskie, had no training at all.

It showed.

On one visit in 2003, inspectors found toddlers throwing a football in a room by themselves. They found Hoskie, who was supposed to be supervising the children, asleep in another room.

Regulators warned Futrell about the hazards of leaving children alone. She promised inspectors at the time that she would train her workers and never put children in danger.

But years later, she started the religious day care where Cummings enrolled Dylan. Futrell used Bethel Temple Church of Deliverance, where her husband was a pastor, to qualify for an exemption in 2009. Now, she no longer had to provide hours of training to all her staff.

Futrell did not respond to calls or emails for comment.

‘I feel there’s no safe place in the world’

Betsy Cummings had Dylan’s name, date of death and his footprints tattooed onto the tops of her feet.Credit: Amanda Voisard for Reveal

After Dylan died, Betsy Cummings spiraled into a deep depression. She couldn’t stop crying. She lost her job in the Navy. She had Dylan’s name, date of death and his small footprints tattooed onto the tops of her feet.

Cummings was heartbroken, but she also was livid at Bethel Temple. When she discovered the day care faced looser rules as a church, she began warning other parents. She’d corner moms in the grocery store to tell them about exemptions for religious day cares and the questions to ask.

What’s more, her faith in organized religion began to crumble.

“I feel there’s no safe place in the world,” Cummings said. “The church is the one place you think will be safe. And the church is probably the worst.”

There were legal consequences for Bethel Temple – at least at first.

The Virginia child care licensing division shut down the day care in 2010. The Norfolk commonwealth’s attorney determined that Dylan’s death was a result of neglect and pressed charges against the day care owner and workers.

Tammy Futrell was charged with two felonies: child neglect and homicide. Several workers, including Dinnetta Feeney and Angel Hoskie, who also worked at the day care, were charged with child neglect.

Cummings threw herself into the legal case, hoping for some sense of justice for Dylan. But a judge eventually dismissed the charges against Futrell and the other day care workers.

In his 2012 written opinion, Judge Charles E. Poston said that while Dylan’s caregivers risked his life by placing him on his stomach with an ill-fitting sheet, they committed no crime. It’s difficult to assign blame in sudden infant death syndrome cases, no matter the circumstances. A ruling of SIDS, by definition, means the cause of death cannot be explained.

But Poston did criticize the looser rules at religious day cares.

He wrote that had Dylan’s day care “been subject to the regulation and inspection required of secular day care centers, many of the SIDS risk factors would not have been present.” Poston said that while the court felt for Cummings, it was up to Virginia lawmakers to change the religious exemption law if they were worried about cases such as Dylan’s.

Cummings was in the courtroom that day. She began to weep when she heard the ruling. And then scream.

“I felt like my son died all over again,” she said.

***

No one was held criminally responsible for Carlos Cardenas’ death, either. Local prosecutors said what happened to him was a tragedy, not a crime. Death investigators wrote that the problem was a licensing issue. They said it was impossible to hold an individual responsible when it was the church’s lack of a supervision policy that killed Carlos.

The Indiana child care licensing division couldn’t do much, either. It took one of the only steps it could, cutting off Praise Fellowship from receiving federal money.

The church, which relied on those federal dollars, became one of 27 religious day cares in Indiana kicked out of the program since 2011. Ninety percent of the children at Praise Fellowship were part of the federal subsidy program, according to court and licensing records, netting the church more than $143,000 from 2010 until 2012.

The church day care voluntarily shut down for good two days after Carlos died.

Reached by phone recently, Praise Fellowship’s pastor, Clarence Hooks, declined to be interviewed, saying, “We have lived and relived this situation, and we don’t feel like living it again.”

Every weekend, Juan Cardenas visits the grave of his son, Carlos. The 1-year-old drowned in a baptismal font at Praise Fellowship Assembly of God day care in Indianapolis in 2012.Credit: Chris Bergin for Reveal

Juan Cardenas still is struggling to get over the death. He and his girlfriend later married and had another child together, but it never filled the void for Cardenas. The two now are separated.

Every weekend, Cardenas visits Carlos’ grave. It’s a marble headstone adorned with snapshots of the beaming boy and, in Spanish, a section of Psalm 23: “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures. He leadeth me beside the still waters. He restoreth my soul.”

Cardenas keeps a photo of his son in his truck’s glove box. At night, he closes his eyes and reaches to the side of his bed, hoping for a moment that Carlos will be there like he used to be, wanting to cuddle.

“There’s not a single word someone can say to make you feel better,” Cardenas said. “No parent can imagine seeing their son dead. That’s what they put me through.”

- Originally appeared at revealnews.org