by Chris Theodore

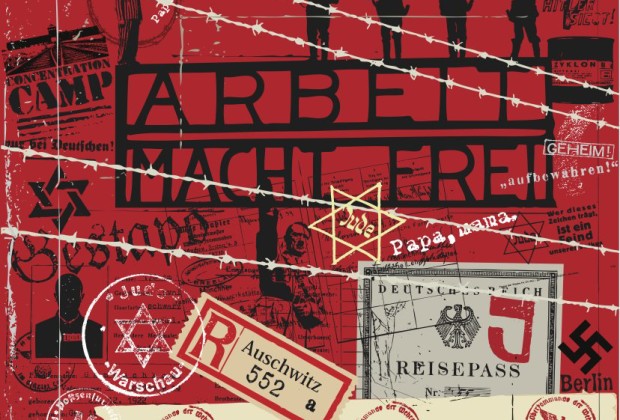

A night ago, I watched a film called The Last Train, the story about the last transport train of German Jews from Berlin to the Auschwitz and Birkenau death camps. It was a transport of 688 people-- grandparents, mothers and fathers, children and even infants who had been rounded up to be "sent east", a gift for Hitler's birthday. Nearly the entire story unfolds in one of the cattle cars. Only after did I realize that I had been mercifully spared the full sensory onslaught of what the trip was really like, including the terror of not being able to escape, and the crushing, moment by moment realization that it was not a dream.

The story was one of the most emotionally devastating portrayals of this nightmare era I've ever seen. You may wonder why talk about a time like this in an issue devoted to the topic of love?

And the answer is that there is much to be gained by remembering this chapter in history, including a sense of how good we have it, and how much remains that is right and just and good in our society. Remembering how absolutely corrupt, broken and evil a society can become, we inevitably come close to the causes of what brought it on and gain something sacred in need of renewal: clarity in our hearts' understanding of right and wrong.

How did it come to be that in a land, not 7,000 miles away from us, not seventy years ago, over vast stretches of land, miles and miles of city streets, acres of countryside, as well as in the tiny confines of a cattle car, there came to be in the hearts of men a different law from what they were born with, which made them capable of doing the things they did?

As I watched the film, I thought about the things I knew that had transpired in history not included in the film-- large and small-- that had brought these families and individuals to a place where they were powerless, unimaginably vulnerable and in a cattle car.

Hitler first attended a meeting of what became the Nazi party as a spy, working at the behest of the government to monitor small political groups. He might not have ever returned, and the Nazi party might have fizzled out, had he not, he wrote in Mein Kampf, received a small post card, which motivated him to return to the next meeting, not as a spy but because he thought the ragtag group could be a platform, and it needed a leader.

This tiny detail makes clear the importance of all our choices, each small detail. In this case a tiny post card may have been the thing upon which matters of absolute life and death for millions of families as precious and sacred as yours and mine, came to depend.

In the years leading up to the time the story takes place, a significant number of Germans accepted in themselves a heart of hatred, suspicion and fear. As my father has said to me thousands of times, "out of the abundance of the heart-- the mouth speaks". And so it was in Germany at the time, giving voice to the hearts of people, came hate-filled language from some in the public eye which polluted their national discourse.

Those using this language justified their tactics as coming from the "depth of their patriotism", or their "frustration" and "impatience" with the "broken system" and with "enemies" within their own country, "enemies" because they happened to look, think or believe differently.

The progression of worse violence and fewer liberties, culminating in the absurdity of families with children rounded up into a cattle car was pushed forward from a belief that democracy was dangerous, slow and inefficient, that division was preferable to the impurity of the blending of ideas. This evolved into intolerance and hatred from which emerged political parties that created a world much worse than one with mere coarse language.

There was a "ghettoization" of people first in the heart, next in language, and finally in reality. It began with people, in their private heart of hearts, thinking about great quantities of "other" people in ways that grouped them together and stripped them of their humanity.

I remember going to a church with my wife in Redlands in which an older man in a wheel chair was asked to share a few words in Sunday School. He said something I thought was so beautiful: "we should be gentle in our speech".

I thought how much hatred could never get off the ground if we were gentle in our speech. There's enough time, there's enough power in gentleness to get our ideas across, but it also includes the transforming power and beauty of love.

In the story, we find older couples, young families, and single people all together. We find families that look like ours, children who look like ours, neighbors who look like ours. We meet them-- they are not a car of fifty people; they are a small seven year old girl who, once inside, tries to think of a different place and world, by remembering a ballerina step she would do with her mom counting time; they are a husband in his seventies who, while holding hands with his wife of many years, thinks back to the time he urged his wife to divorce him and go to America and she says she will not leave his side; it is a beautiful baby named David, with his mother, father and sister, Nina, who tells her daddy, a boxer, that she packed away his medals so that he can one day show them to David. Days later, the baby dies of dehydration-- true to the reality of what happened countless times.

As I witnessed more of the story, I found it impossible to feel like I was not there with them, and hoped to be able to prevent something like this from ever happening again. I prayed to have the insight to recognize similar but perhaps less obvious threats to freedom.

When we lump together a person who doesn't share our views into a "group", it would be wise to remember who, in the scope of history, also did this. To view someone as "not within the family of humanity" is a step to seeing them inferior to us, which is a step closer to wishing that they did not exist. We should therefore understand "what the end game" can be in this process. In Germany, this "separation" ended with the handicapped, elderly and others being considered Lebensunwertes Leben, "life unworthy of life", culminating in policies of mass murder.

From the abundance of the heart, hateful speech with violent imagery was a bend in the twisted road to Auschwitz. This is why today's political rhetoric that uses seemingly harmless terms like "reload" should be called out for what it is: an attempt to hide the emptiness and lack of merit of the speaker's ideas.

When I was 27, I visited Krakow Poland and then visited Auschwitz and Birkenau. I walked past wooden bunks, barracks, gurneys, stacks of suitcases, glasses and mountains of hair left on display from a transport from Holland. At Birkenau, I walked down some of the steps of the half-destroyed gas chambers, dynamited by departing German soldiers, and imagined the scenes that had took place there.

Prior to the time this story took place was a society in economic turmoil, confusion and uncertainty. One school of political thought was to "solve" these problems by relinquishing individual freedoms for the sake of order and "security". This response paid lip service to religious institutions-- in speeches, and public pronouncements-- but the philosophy, at its heart, equated love with weakness. As time went on, the Nazi philosophy paid less lip service to the religious institutions, and openly ridiculed the principles many of these institutions professed to be based upon: kindness, fairness, charity-- names we also use to describe love. There was a time, history shows us that the religious institutions, the churches, could have rallied together and publicly condemned Nazism from the pulpit, and ended the party. But these institutions did not in fact embody or promote the teachings of Jesus.

What does it say about who we are that we profess to be a nation aligned with the teachings of a man who said "love your enemies", but our government is able to channel half of all taxes from every household to the military, under the guise of "protection from our enemies"-- without widespread dissent from the American pulpit and people?

Where does all of the support for more and more military spending come from? Ironically, it may come in part from the pulpit of some churches, who perhaps unknowingly work at the behest of the Halliburtons and weapons manufacturers by pointing a finger at the Muslim world as the threat that will end life for us all. In reality it is not one of the world's oldest religions, whose scripture no more promotes violence than our own, that poses any real threat to us. The real threat is division, making America incapable of coming together to recognize and solve its problems.

The story of the families in this last train from Berlin, as does the broad teaching of history, shows there is a progression of events like tracks on a railroad-- including that what is believed to be "not right" which people do not do anything about can become something "not right" that they cannot do anything about.

And so what do we do with today's economic turmoil, confusion, and uncertainty? One response is to approach it with love. It is to not seek out an "other" or an "enemy". And instead, use the considerable energy that is thus conserved, to solve the real problems. As Chris Hedges discusses in his article in this issue, love is not a passive, weak response or political ideal. Perhaps the reality is that our politics, our economics, indeed our communities and families and relationships all need more love in them.

To those who would say that love-- as a political philosophy-- makes us vulnerable to the North Koreas of the world, I would respond that it is the North Koreas of the world which can no longer resist the power of love. To those who dredge up 15th century Machiavelli as the proof that we must be cruel in order to lead, I would respond by saying Niccolo was not living at a time when there was something called global thermonuclear war, in which 400 million lives can be vaporized by a Machiavelli-reading fool believing the prince willing to be cruelest always wins.

Today as you read this, what is universally being thrown away are Machavellian beliefs-- from an instinctive sense of self-preservation and instinctive sense of what is possible-- and what is being picked up around the world is the millennia-old story of love. You see it in the ideals of the posters around the world, such as these words on a poster in New York: "Fall in love. Falling in love is the ultimate act of resistance to today's tedious, socially restrictive, culturally constrictive, humanely meaningless world. Fight against these cultural restraints that would cripple and smother our desires. So fall in love today with [others], with music, with ambition, with yourself, with…life!"

At one point, the train car stops at a station. The men and women who are closest to the bars and barbed wire of the small window plead with anyone for water or food. They continue to do so until the soldiers, angry at the noise shoot the cattle car. Instead of imagining what this does, we see the inside of the car-- a woman has been shot, she's bloody, and is dead. The little seven year old who days earlier was practicing her ballet, whose mother told her to think of other things, is screaming hysterically. This scene reminds me of the wall of ignorance we have put up between ourselves and some of the people in the world who suffer today. Living in the world today we hear of tragedies and unspeakable injustice-- but it is conveniently out of our sight. There was something horrific about how the story lingered after the soldier's decision to shoot into the cattle car before going through the wall to show the effect on the people inside from the shooting. It somehow reminded me of the many walls that I never have to go through and witness what is behind them.

Other times the train stops at stations where we see people "from the outside world" going about their business, glancing at the hopeless, desperate people staring at them or begging for food or water as if they are-- alien, separate. Out of the abundance of the heart, the mouth speaks, and reality follows. Elsewhere at the station, soldiers from the train are drinking cold beer in glasses along with sausage and bread. Of course the magnitude of the horror is impossible to feel if we are not there-- but as I travelled with these families in the story, I felt welling inside me some new determination-- the train car reminded me of life-- now. As the story progresses some of the men and women begin to use a smuggled axe to cut through the bottom of the cattle car. The axe falls through the hole so they begin to use a stone.

If you have ever felt something instinctively you will understand that at a certain point, some of the people in the car start to know that they are approaching their destination. As the train stops at the final station before Auschwitz, where the train is to stop for just a few minutes, the people have managed to cut open a hole large enough so that a child or a "slender woman" can get through. At this point, there is a pile of bodies in the car, the men and women have begun to drink their own urine to stay alive, and most simply want the car to get to its destination so they can die. No one in the car resembles the person they were just a week or ten days earlier. They have witnessed the dismantling of everything precious to them. On the car a child reads someone's words carved into the wood wall that say, "I dreamed a terrible dream which has come true". Only two from the car leave by the carved out hole. A woman named Ruth and the seven year old girl, whose parents force her to leave despite her requests to stay with them.

It is night and as the two fall onto the tracks under the train it's clear that they may be shot at any moment as there is light from the station. Sensing the danger of the two under the train or perhaps simply hoping for food and water the people again beg for food and water which brings the soldiers over to the side of the train. We see the young girl's mother sticking her head out of the hole to watch to see if her daughter will make it. Her face looks beaten and numb and dead but her eyes are hoping that she is able to see her daughter make it to safety. As the two run away from the train the young girl falls and her foot gets caught in the track. Not far away we see a train coming down the same track where she has fallen and a solider hears the two struggling, shouts that he hears something and seeks them out and aims his rifle at them. Just as he is about to shoot, the young girl leaves her shoe in the track and runs away, the train passes between them and the soldier is shot accidentally by others trying to shoot at the two who have escaped. The mother of the girl sees all of this and when she is lifted back in, she tells her husband and the rest what she saw, saying "it was a miracle". We see the young girl and Ruth helped away from the train by partisans who we later learn go there nearly every night to help people escaping as it is "the last station" before Auschwitz. In the end, the car arrives, nearly half are dead and those barely alive, stripped of their humanity, hanging on to whatever they can, are hurried off the train by prisoner guards. We don't know if the young girl and Ruth live-- and I don't know if the story is true-- but I know that things like this happened.

And so what does all this mean for us right now? Well, those people who found themselves in that train were once where you and I are now: enjoying simple pleasures-- gardening, a meal outside with family and friends, warmed by the sun on beautiful days, felt the happiness of seeing their children grow, families enjoying the longevity of their union. This beautiful world began to change. If there are things we can do now so that there is less hatred, less injustice, less misery and suffering in our world now-- then we must do these things. If not, are we any better than the people in the station who saw the fathers and mothers pleading for bread and water for their children and did nothing? If we do not do what we can do now, have we learned anything from the suffering of others like those in the last train?

There's something else. As I witnessed what I would never want to see happen to any family-- happen to these poor people in this story-- and as I realized that this depiction-- with its camera and lights and actors and lunch vans-- depicted what happened to people in reality, I felt a deep sense of determination well up inside of me. That is, I became even more determined to see to it The Reader Magazine someday reaches all 308 million Americans. Because I know that telling 308 million Americans stories like this one-- will bring about something you might call the exact opposite of the effect the penny post card had on Hitler-- that is, it may spark the mind of a person to change the world forever, for good.

Email:

Email: