Laws allowing parents to leave low-performing schools or in some cases exert more control over them remain on the books, but changes to the state’s evaluation system have made them unusable.

by Will Huntsberry

When a school showed up on the state’s list of lowest-performing schools in years past, parents had several options spelled out in state law: They had the right to shake up the school’s staff or change its curriculum if they gained enough signatures; they were also automatically notified their school was on the list, and provided with options for their child to attend a higher-performing school.

Those laws remain on the books, but changes to the state’s evaluation system – which grades schools across several categories – have made them unusable.

Political winds have swung wildly against charter schools, which drained money from cash-strapped local school districts, in recent years. And as pressure has mounted to increase accountability for charters, which have been subject to little oversight, accountability for traditional public schools has quietly ratcheted down.

At the core of the changing policy landscape sits an essential question: Is it possible for educators to eliminate the achievement gap for black, brown and poor kids to give them an equal shot at success? The ultra-high pressure accountability of the federal No Child Left Behind law did not do the job. Will the light touch of no accountability work any better?

Under the old system, the state created the list of lowest performing schools by using the Academic Performance Index, or API score, which largely measured a school’s test scores. Now, schools are measured using the California School Dashboard, which gives a more nuanced picture of success that includes absentee and suspension data. The dashboard came online last school year.

The old accountability laws used API score and another measure called Adequate Yearly Progress as their underpinnings. Since the laws don’t reference dashboard criteria, they are unenforceable.

The new system is transparent, but it’s not accountable, argues Bill Lucia, the president of EdVoice, a non-profit aligned with charter school supporters.

“In the health world, we take a patient’s temperature – 103 degrees is pretty sick. That’s like having all red [the worst ranking] on the dashboard,” he said. “Transparency is taking the temperature. Accountability would be: Someone has to call the ambulance, did it show up within six minutes, did it make it to the ER, was the patient treated, did they get better? Is there any evidence of ongoing care besides creating the dashboard?”

But stepping back and letting teachers do their job is exactly how to help students perform better, said Ed Sibby, a former teacher and communications consultant for the California Teachers Association, a statewide union. He thinks the list is not helpful in the first place.

“As teachers we don’t look at our schools in terms of comparison with other schools and definitely not in terms of ‘failing’ or ‘not failing.’ The labels don’t help students at all, frankly,” he said. “We measure our students by their strengths in the classroom and want to move away from standardization.”

I asked Sibby if some terms, like “achievement gap,” weren’t important for maintaining the urgency required to help struggling schools. He bristled at the term. “This idea of the ‘achievement gap,’ it has a lot of pejoratives for me. That said, as a white male who went to public schools my entire life, I know I got a different education than some people.”

When a school previously ended up on the list, the Open Enrollment Act automatically kicked in. Parents had to be notified their child’s school was on the list and be given the option to transfer out. If the school stayed on the list for a number of years, the Parent Empowerment Act also kicked in. That let parents organize petition drives that would allow them to reconstitute the school. They might change the curriculum, seek to replace the school’s staff or, in the most extreme option, turn the school into a charter.

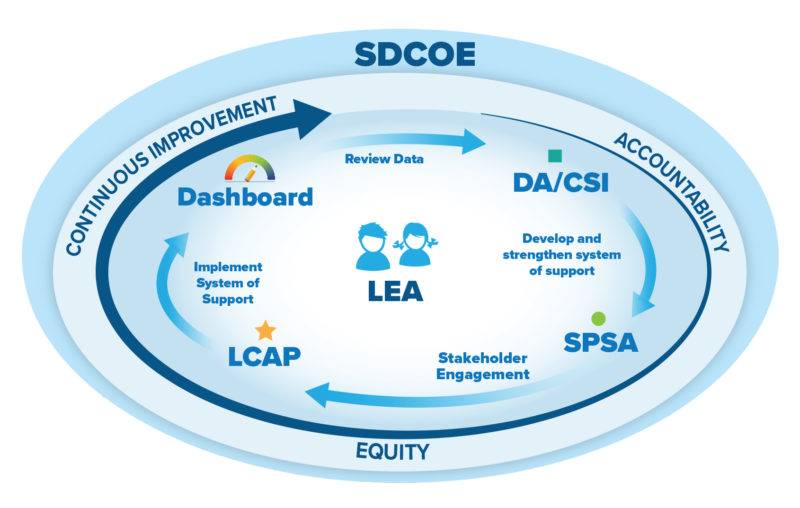

Now when a school ends up on the list, it enters a “continuous improvement” program, according to state guidelines. This chart from the San Diego County Office of Education explains the cycle.

School districts get a small amount of money, which is filtered through the County Office of Education, to try to examine the root causes for a school’s failure to thrive. Districts are then supposed to engage parents for ideas and implement solutions on their own, without additional money. Then the data gets reviewed again and, in the ideal world, the school will have improved.

Parents no longer have to be notified their school is on the list.

Aside from the tens of thousands of dollars schools get to study the problem, this is not different than how any school in California theoretically operates. Administrators, principals and teachers are constantly examining data to figure out where they need to improve and then looking for results.

Officials with the California Department of Education declined to comment for this story.

Schools have four years to exit the list. If they don’t, schools “may be required to conduct a new school-level comprehensive needs assessment,” according to state documents, and may be required to partner with an outside organization to help them improve. After that, “the plan does not indicate next steps if schools still don’t improve,” according to an analysis by the Education Trust – West, a non-profit group.

Schools make it onto the list if they are ranked worst – on the dashboard it’s red – in all of five categories, or all but one. They make it off the list if they receive a middle ranking (yellow) in at least two categories. The five categories are absenteeism, suspensions, math, English and English-learner progress.

High schools with graduation rates of less than 67 percent also automatically make the list.

“Our goal is to have a quality school in every neighborhood and if a school is performing low on lots of measures it’s obviously not a quality school,” John Lee Evans, a board trustee for San Diego Unified School District, told me last month. “We need to focus extra attention and resources on those schools within the limited budget we have.”

In San Diego Unified, nine traditional public schools are on the list. Countywide, it’s 58 schools, including charters.

Seth Litt, executive director of Parent Revolution, argues that the Parent Empowerment Act may still be viable. His group helped parents organize several campaigns to use the law in the Los Angeles area. He pointed to a court case in Anaheim that was decided during the transition from API to the new dashboard. That case ruled that even without new API data, the law was still valid. But now that the new dashboard is up and running, state legislators would have to clarify what dashboard metrics make the law kick in.

Letting the laws become impossible to access because of technicalities is a “backdoor way” to change the law, he said.

“Lawmakers have been negligent and made these laws hard to access, without proposing new laws that would, essentially, strip rights from families,” Litt said. “But if that’s what they intend to do that would be the more transparent path.”

Will Huntsberry is a reporter for Voice of San Diego. He writes about education, schools and children in San Diego County. Please reach out with tips or ideas to willh@vosd.org or 619-693-6249.

First appeared on Voiceofsandiego.org

(909) 335-8100 ·

(909) 335-8100 ·  (909) 335-6777

(909) 335-6777 Email:

Email: