by Garrett Carr

I grew up near Ireland’s border when it was a hard border, though we had yet to learn the term. The border was guarded with customs posts and military fortifications, and often there were searches and questions. Many people are determined to avoid seeing such infrastructure on the border again after the UK leaves the EU.

The new draft deal between Theresa May and the EU seems to have been shaped in important ways by this determination. Assuming that the deal is accepted by Westminster – a big assumption – there is still a lot left undecided in the 585 page document, and gaps to be filled during future negotiations. What will Ireland’s border look like after Brexit? It still feels as if anything is possible.

The border was created in 1922 when 26 of Ireland’s counties became an independent state, while six remained in the United Kingdom. It was a hard border to some extent or another until two events in the 1990s: the peace process and the creation of a customs union across Europe, including both parts of Ireland.

A sense of place

Ireland’s border got me thinking about aspects of place and space. Not all coordinates are equal. Two Irish hedgerows might look the same, with the same March songbirds and September berries, but one is just a hedgerow, whereas the other might be the frontier between two countries. That hedgerow is actually marked on the map, with a borderline symbol that is loaded with meaning and contention.

Recently I returned to Ireland’s border to walk it, map it and write a book. I was interested in the people for whom the borderland is home. I became fascinated by paths they had cut across this invisible line, and the homemade bridges they had placed across streams that straddle the 310-mile border.

In contrast, I also mapped the border’s defensive architecture. My project took on some urgency when the UK voted to leave the EU, when suddenly this border of rivers, bogs, farms and forests became central to the way that would happen. It had always been my intention to give border voices a platform, and now more people were interested in listening.

This year, American Suzanne Lacy was artist-in-residence for the Belfast International Arts Festival and was commissioned to produce work on Ireland’s border, in collaboration with border communities. Lacy is an artist of public practice – by getting people together for discussions, events, activities, she choreographs conversations.

She brought me on board for part of the project called the Border People’s Parliament. This event was held in the grand marble hall of Stormont, Northern Ireland’s parliament. We gathered around 150 people from the borderland, aiming for a mix of backgrounds and ages. On the night we ate a meal together and I conducted some interviews and made recordings.

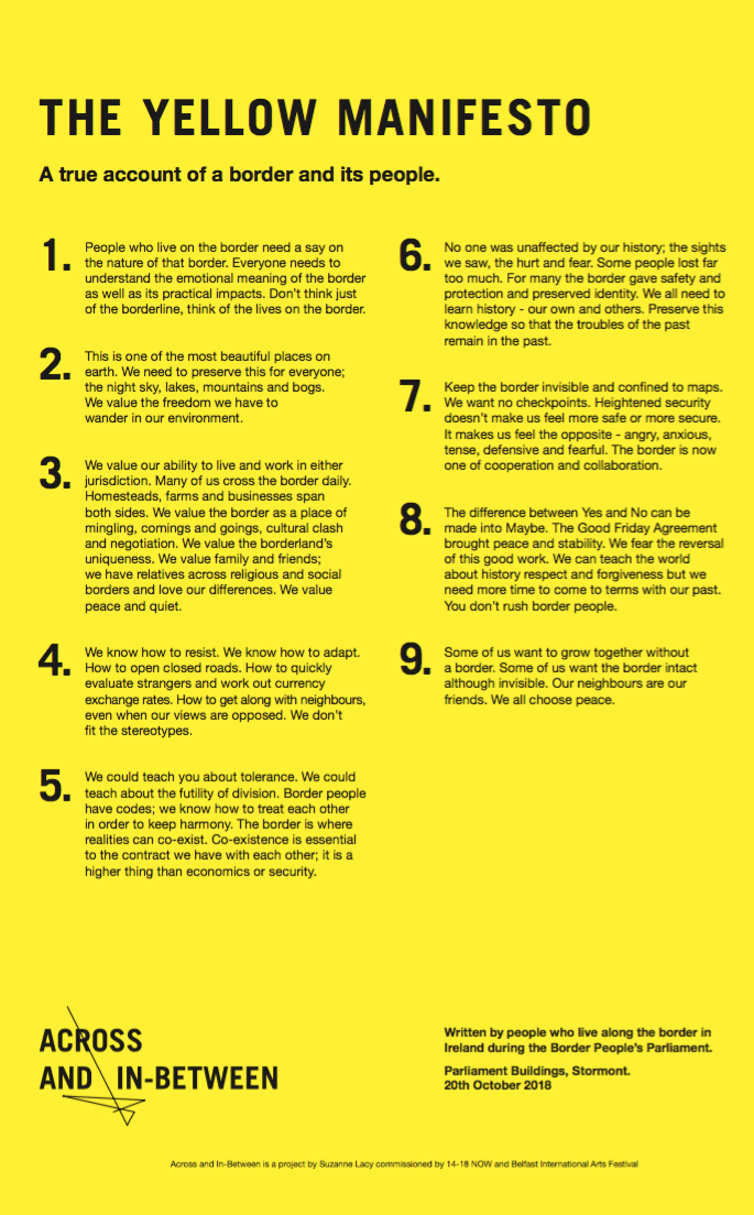

The border people’s manifesto

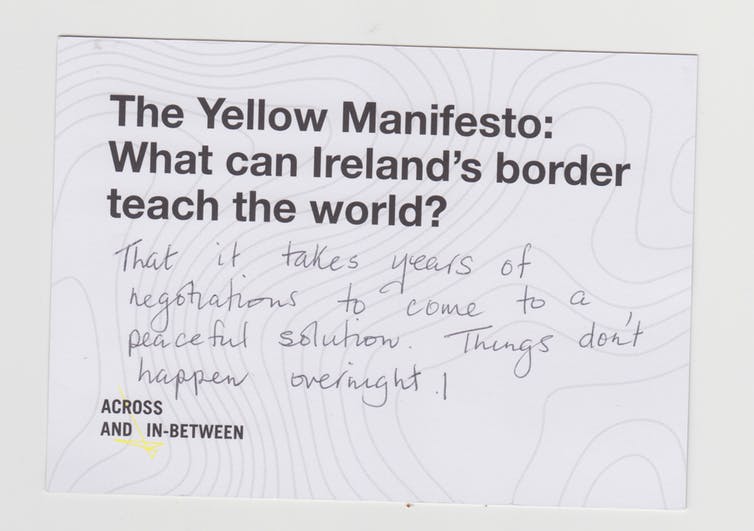

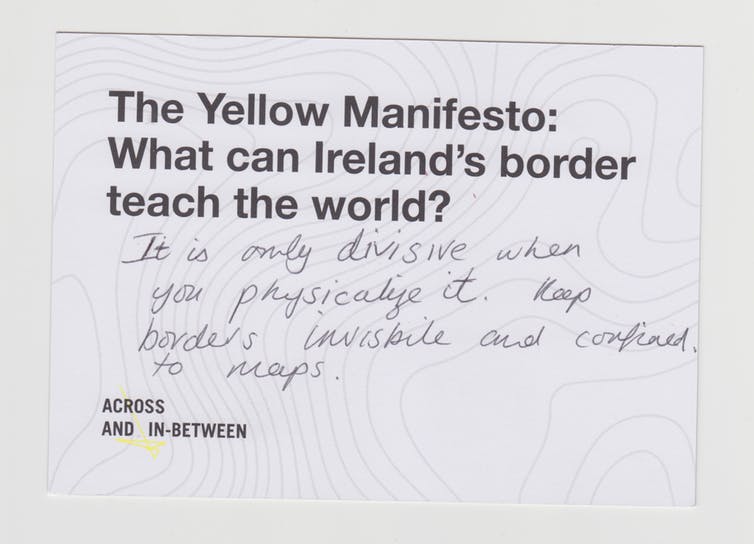

Participants were asked to consider various questions about the borderland and their lives on it. For the last part of the night, they were given sheets of paper on which to respond to our questions. Some wrote postcard-length comments, others extended letters. I was charged with taking their words and distilling them into a single border people’s manifesto.

Author provided

In creating the manifesto, I wanted to use border people’s own phrases, with as little meddling as possible. I changed the point-of-view voice into first person plural – “we” and “our” – but in every other way endeavoured to be true to the source material, capturing both the overall message and the language in which it was expressed. I also wanted to capture some of the tone and the accent of borderland voices, hence the appearance of well-worn phrases such as: “You don’t rush border people”.

The manifesto had to be turned around quickly and I had no idea at the beginning whether it would be a smooth or difficult task. I don’t think anything like it had been done before – and certainly not on Ireland’s border.

Author provided

Open and invisible

I had been concerned that there would be much disagreement in the comments – equally valid but oppositional statements that would never sit together in the same document. But this was not really an issue in the end. There were pro and anti-Brexit voices, but both were united in calling for the border to remain open whatever the future. The term “invisible border” was used often.

Points of pride emerged. The border landscape’s beauty was often mentioned alongside a desire to preserve it. Border people’s tolerance, neighbourliness and an ability to get along despite political differences were frequently referenced. Several said that we should all learn history – learn it so we don’t have to repeat it, but at the same time remember to live for the future.

Author provided

All of this and more went into the nine points of the manifesto. The colour yellow was a theme of all Suzanne Lacy’s Across and In-between border projects (which also included a film, The Yellow Line, projected on to the side of the Ulster Museum in Belfast) and so the document came to be called the Yellow Manifesto.

It has proved popular on social media and in the press after being launched on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme by Lacy on October 23 2018. Immediately afterwards she travelled to the Houses of Parliament and gave copies to MPs.

In Westminster it seems the border is constantly discussed – but only as a problem or an obstacle to Brexit. For me and the population of the borderland, it is important to let people see that it is also a home, the basis of livelihoods and even a place that is loved.

Originally appeared in The Conversation | Image Credit: Eric Jones/Geograph.ie

(909) 335-8100 ·

(909) 335-8100 ·  (909) 335-6777

(909) 335-6777 Email:

Email: