by Karen Hunt

As we wear poppies to mark the end of World War I, we should ask ourselves who we are being asked to commemorate. Despite four years of television programmes, exhibitions, art installations and local history projects, we still seem to find it easier to focus on the trenches than the home front, on men rather than women – and, among the women, on munition workers and nurses rather than housewives.

The stories remain largely masculine – despite the large amount of money put into commemoration through the Heritage Lottery Fund, large-scale projects including the BBC’s World War One at Home and the various World War One Engagement Centres, as well as the many academic studies by historians revising our understanding of how the war was experienced across Britain and the world.

In the end, it is the “mud and blood” narrative that seems to trump every other story. But we would have a better understanding of Britain’s experience of the world’s first “total war” if we widened our focus. One way to do this is to focus on women on Britain’s first home front.

Women making boots in the Royal Army Clothing Department in London. Imperial War Museum (IWM), CC BY-ND

In researching my essay, A Heroine at Home: The Housewife on the First World War Home Front, I found that during the Great War about 1.66m women entered the workforce, swelling the number of women workers to more than 6m.

These new workers were significant, representing major changes in how individuals and households lived. These women undertook traditional women’s work, new wartime jobs and, less often, took over “for the duration” what had been considered to be men’s jobs. It is the last group – whether munition workers or tram conductors – who have garnered most attention in commemorative activity.

But there was another, larger group of women who are often overlooked. Census data from 1911 and 1921 (the two closest to the war), which are not available online, reveal a sizeable number of women who were not in paid employment. Many of them were housewives, with the responsibility of running the household, however substantial or inadequate their income. Not every woman lived in a family household, but whether she was a lodger, lived alone or in a shared female household, it was almost always a woman who bore the responsibilities of running the house.

How many women are we talking about, and how do they compare to the number of women in the wartime workforce? Adding together the numbers of non-working females over 10-12 years old (the definition of an adult worker was changed between censuses) with those of married and widowed women workers – both of whom would have had to run households as well as working – means there were 10.63m possible housewives in England and Wales in 1911 and 11.75m by 1921.

Even deducting the women who officially entered the workforce during the war, there were considerably more housewives than women war workers; and, of course, even single women workers had to feed themselves and attend to domestic labour or find someone to do it for them (hence the importance of hostels for newly-recruited women munition workers).

So what happens if we put these housewives back into the story of the Great War?

Feeding morale

Housewives had a crucial role to play at a time when food essentially was weaponised. Economic blockades were used systematically by both sides. The purpose was to starve out the enemy, particularly civilians, and undermine morale – the thinking was that hunger would drive the population to demand an end to the war. In turn, this would have had a catastrophic effect on military morale. Soldiers fighting to defend their homes and families might mutiny or desert if they knew their loved ones were suffering at home.

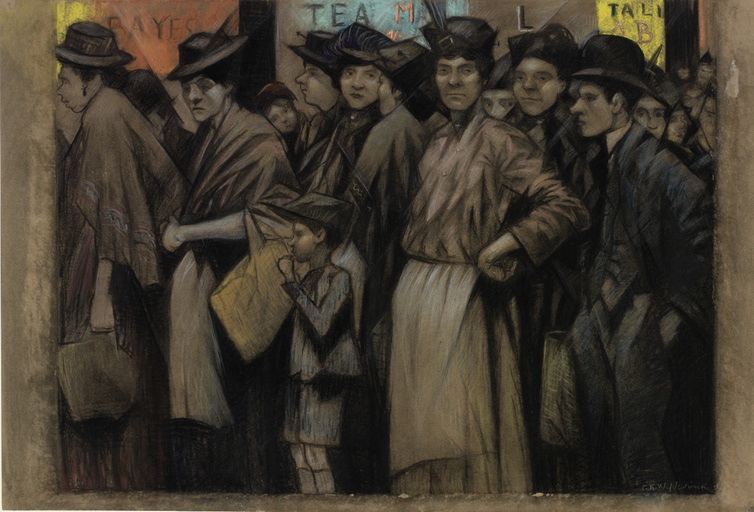

‘The Food Queue.’ C R W Nevinson (1918) Imperial War Museum (IWM), CC BY-ND

Without understanding this aspect of the world’s first experience of modern war, we miss the significant role that civilian morale and its interdependence with military morale has for warfare. This all begins with the mundane and relentless task of feeding oneself and one’s household as rising prices, poor distribution and even a dearth of basic foods and fuel made shopping and cooking an exhausting struggle for those whose responsibility this had always been: women, specifically housewives.

Everyday life, specifically the getting of food, was crucial to the winning or losing of a “total war”. That was why a wartime poster urged: “The Kitchen is the Key to Victory.” This was a battle in which the nation’s survival depended on the housewife’s actions: how she dealt with rocketing food prices and widespread shortages mattered not just to her own family but to the home front as a whole.

Exploring everyday life on the diverse home fronts of the Great War gives us a new way of understanding the war itself. We should put the housewife back into the stories we tell of the Great War and include her in what we commemorate.

Originally appeared in The Conversation | Image: Imperial War Museum (IWM)/cc

(909) 335-8100 ·

(909) 335-8100 ·  (909) 335-6777

(909) 335-6777 Email:

Email: